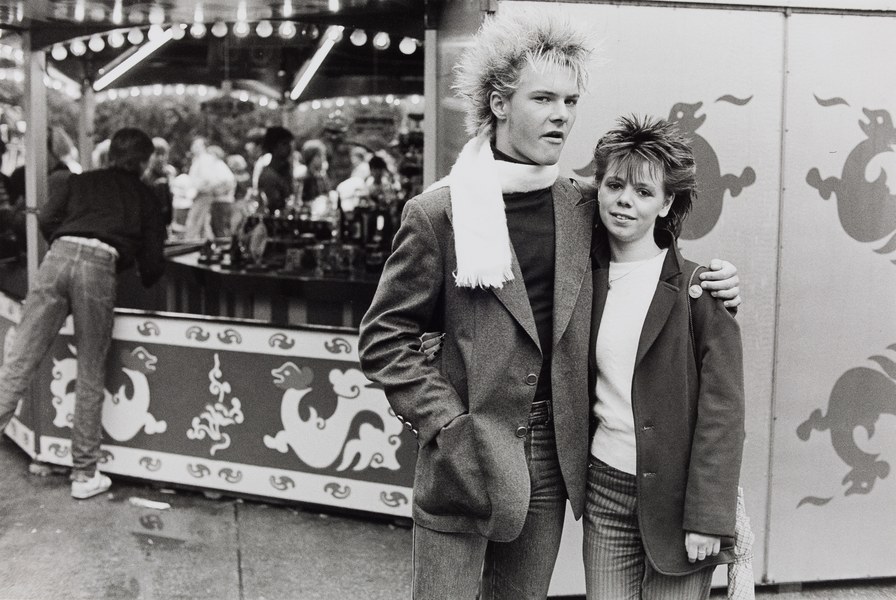

Christian Borchert, Junges Paar zum "Fest an der Panke", Berlin-Pankow 1985

Christian Borchert (1942–2000)

April 27 – June 2, 2018

When Christian Borchert (*1942 in Dresden, † 2000 in Berlin) had a fatal swimming accident in the summer of 2000 aged 58, he left behind a systematized and sophisticated East German chronicle of his epoch. At that point, his archive was already unusually well structured, comprising 230,000 black-and-white negatives, 18,000 prints (which he called working prints), and about 2,300 35-mm slides. “I enjoyed collecting and organizing,” he said four years previously in an interview. His working prints were, he said, to which he not only kept adding new photographs, but which he always looked through and organized them in new thematic contexts: “I need time,” he further described his method, “before I’m clear in my mind whether a photograph is my photograph —I often reject pictures, and then retrieve them again.”

Borchert’s artistic career really began in 1975, when he left his job as a photo reporter at the popular weekly GDR magazine “Neue Berliner Illustrierte”. In that year, he finished a correspondence degree course at Hochschule für Grafik und Buchkunst in Leipzig, the only art school in any Eastern bloc country after 1947 that also trained photographers. The guiding principle of the school was to link a claim to depict reality with art, and the realist method of a photographer like August Sander in particular turned out to be an artistic heritage that Christian Borchert appropriated for himself. Borchert succeeds in suggestively charging Sander’s objective style by drawing inspiration from the works of Paul Strand and Irving Penn.

He started to work freelance and commissioned himself. Beginning in 1977, he documented the cultural and social history of the GDR in a “GDR Collection,” which he organized thematically. The result were the famous family portraits, the scenes of everyday life, the artist portraits, and the landscape documents. His stringently objective visual vocabulary is characterized by both sympathetic distance to the motif and respect for it. The photographs are evidence of an unfaltering determination not to suggest any false authenticity of an immediate existence, and in their frontality they also admit to being to a certain degree staged. His photographs in the group show “Wir stellen junge Fotografen vor,” which took place in autumn 1974 in Berlin’s Stadtbibliothek, caused considerable scandal and discussion.

In the path-breaking exhibition “Geschlossene Gesellschaft” (Berlinische Galerie, 2012) about the history of photography in the GDR as a non-conformist artistic means of expression, Christian Borchert’s work took a prominent position, and belonged to the most frequently reproduced pictures of the exhibition. The exhibition transports a sense of a stuck, frozen era, and Christian Borchert produced his own sequel to this sense after Germany’s unification. Taking his earlier system further, he returned to the motifs for a second time, especially to the families. In this way, he did not just picture the survival of the individual within collectives, but also showed a society in transformation into an uncertain future and hope. His eye for the “distinctions” is sectarian and not psychological. In their linking of today and yesterday, his works offer an overall view – with a claim to eternity – of voluntary and involuntary distinction of classes.

After showing Manfred Paul in their showroom, Loock is now presenting Christian Borchert– another artist who positioned himself against the veristic perspectives on the reality of the GDR, and took the principle of being an eye witness seriously, which brought him into conflict with the staged and slightly sugarcoated pictorial worlds of socialist propaganda. The quality of this oeuvre is not just that it documents a disappeared country and system, but that it reveals and preserves the artists’s own world with stubbornness and resistance.

Text by Sassa Trültzsch, Berlin, 2018